As a prelude to the UK Festival of Cuban Cinema in March 2024, we highlight some stand-out films in revolutionary Cuba’s cinematic history

Before the Revolution, cinema in Cuba was largely Hollywood-made. Within three months, the new government declared the importance of state support for film and other forms of culture, and established the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC). The new national cultural policy would free art from commercial ties, free artists to “talk about the great conflicts of man and mankind, dramatically and contemporarily”.

The creation of ICAIC – with its integrationist and decolonising outlook to culture – brought a national film industry by the early 1960s, a dream that founding figures like Julio García Espinosa, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Alfredo Guevara, José Massip and Jorge Haydu shared while making El Megano, a film about the exploitation of coal-workers in 1955, a possible blueprint for the new revolutionary cinema.

Cuban film-makers were tasked not just with reflecting the changing society but with helping to transform it – dismantling the old system of social relations, set by centuries of colonisation, and forging a new national identity in the most visual way. Experimentation was encouraged and influences include the aesthetics of Cinema Novo from Brazil, 1950s English Free Cinema, the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism. The big screen could now give voice and space to the previously marginalised: workers, women, farmers, the black population, as well as revolutionary heroes. For the first decade film-makers asked: who are we? How do we want to live?

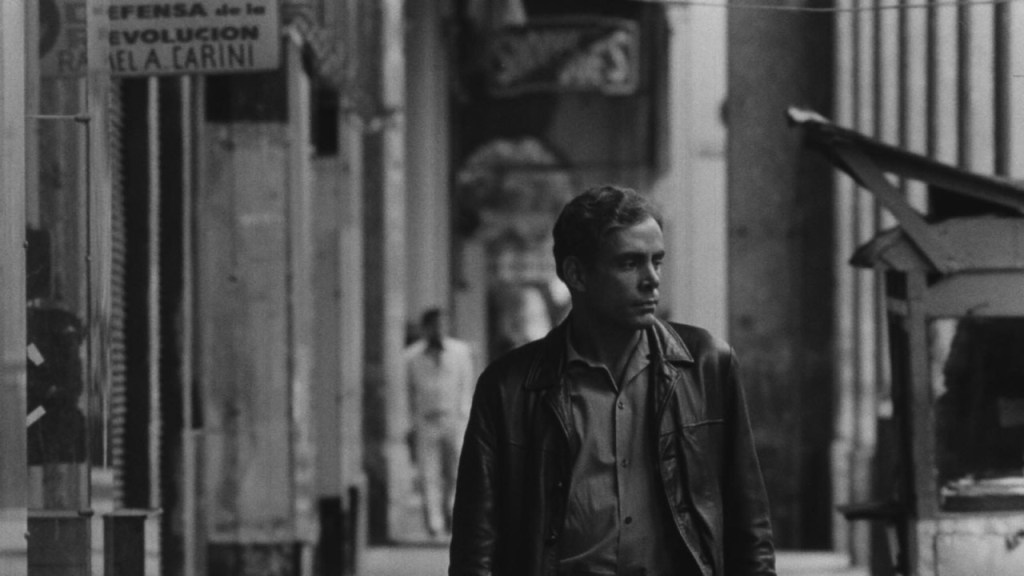

The films challenged, educated and entertained, directly addressing Cubans across the island. Hilarious criticism of the absurdities of public administration procedures in Death of a Bureaucrat come to mind, as well as the more serious Memories of Underdevelopment whose bourgeois protagonist alienates himself from joining in the new social project.

The innovative documentaries and newsreels of director Santiago Álvarez were crucial for putting together images and sound to explain complex situations – watch Now! (1965), for example, about US racist violence. The People’s Encyclopaedia Department was set up to rethink the role and place of popular culture, including Afro-Cuban religions, leading to a new anthropological aesthetic vision through documentary making – seen in José Massip’s Suite Yoruba in 1962, and in films by Rogelio París, Nicholas Landrián and Sara Gómez.

Mobile cinemas were taken into the countryside where some watched films for the first time. ICAIC set up an animation studio to make their own cartoons and later animation features, especially the work of Juan Padrón. In 1969, the ICAIC Sound Experimentation Group (GESI) emerged as a creative hub making music for the new cinema, experimenting with international, classical and Cuban genres headed by Leo Brouwer.

If the 60s were about subverting the past and creating the new, the 70s were about examining Cuba’s colonial past as well as contemporary everyday relations close up. The period 1971-76 was dubbed the “five grey years”, allegedly when socialist realism exerted too much influence.

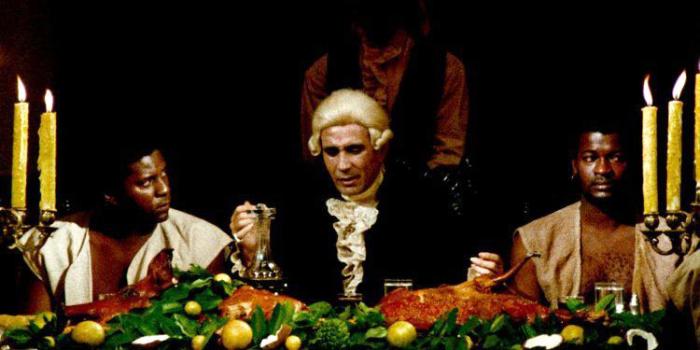

Although dismissed by some as an era when culture became less critical of the revolutionary process, it certainly delivered some gems. One Way or Another (1974) by Sara Gómez, the first feature by a black female director, reflected the results of certain social transformations and the intersections of race, class, gender. The Man from Maisinicú by Manuel Pérez showed the people’s struggle against counter-revolutionary gangs. Alea looked at slavery and religion in The Last Supper, and Sergio Giral made his trilogy on slavery The Other Francisco, Rancheador and Maluala. ‘The Brigadista’ by Manuel Octavio Gómez was a personal take on the literacy campaign, while Pastor Vega’s Portrait of Teresa confronted sexist stereotyping.

December 1979 saw the first International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana, which continues to be an important annual event showing Latin America through the lenses of its own film-makers.

The creation of the new Ministry of Culture in 1976 coincided with more discussion across the arts of problems in society. Film-maker Julio García Espinosa became president of ICAIC from the early 80s, aiming to bring more diversity. He had, in 1969, coined the concept of “imperfect cinema”, rejecting technical perfectionism and embracing defects to democratise cinema.

In the 1980s Cubans laughed at themselves and individual conflicts in urban comedies such as House Swap, Plaf! Or Too Afraid of Life and Adorable Lies, but also explored problems in social relations such as in Up to a Point and A Girlfriend for David. After the Mariel boatlift in 1981 of Cuban migrants to the US, the issue of migration took centre-stage for the first time in Distance.

In 1986 the International School of Film and Television (EICTV) opened in San Antonio de los Baños near Havana, aiming to develop film and TV with a decolonising perspective and offering scholarships to students across the developing world.

In the 1990s the Special Period economic crisis prompted talk of ICAIC being dissolved – there were almost no funds to make films. Film-makers sought financial support abroad, which sometimes meant Cuba was presented through foreign eyes, but directors gained space to give their personal view.

In Strawberry and Chocolate (1993), Tomas Alea got the whole country to rethink attitudes to homosexuality and about who could be a revolutionary. Guantanamera (1995) looked at the effects of the economic crisis on relations between people. These demonstrate how Cuba was openly exploring problems of bureaucracy, corruption, intolerance and lack of material resources, via film leading to national debate. Waiting List (2000) was another example. Other themes at the time included migration, housing, and the rise of African religious expression.

Meanwhile in 1993, Televisión Serrana was set up in a coffee-producing area in the Sierra Maestra mountains. A collective using TV and video to try to solve problems in the region and give voice to the rural communityʼs needs, beliefs, identity, it has made over 500 documentaries.

The 00s brought an upturn in the economy, but cinema examined more closely the everyday struggles in families and relationships, such as in Honey for Ochún, Barrio Cuba, and Viva Cuba. In some films migration and the effects of tourism on daily life on the island weighed heavily. In Suite Habana (2003) Fernando Pérez showed a sad beauty in the lives and interactions of eight residents despite the damage wrought by material shortages. Jorge Luis Sánchez’s music biopic Benny (2006) about Benny Moré, arguably Cuba’s most famous singer, laid bare the racism in the country pre-1959 but was also a means to discuss contemporary issues for Cubans facing the lure of the US music industry.

In 2003 the Cine Pobre film festival was launched in Gibara near Holguín, 800km from Havana. Now known as Gibara International Film Festival, the ethos is still to show low budget films from Cuba and elsewhere.

The 2010s onwards brought a number of films about gay and transgender life and challenges in Ticket to Paradise, Fatima or the Park of Fraternity and Wedding Dress. Ernesto Darañas’s Behaviour (2014) asked serious social questions about care for young people. Fernando Pérez’s José Martí, the Eye of the Canary, showed colonial injustice through the young Marti’s eyes. Interestingly, the Cuban film most successful in attracting foreign finance at the time was Juan of the Dead (2011), a zombie comedy set in Havana.

The last 20 years brought new technologies in the making and distribution of films, as well as new ways of financing and promoting them. Home and online viewing has changed the world of cinema for good across the world. TV drama in Cuba has also taken up the role of exploring, with its still huge audiences, contemporary issues including inequality, intergenerational conflict and disability. In 2019 a new framework was introduced for independent film-makers and productions on the island. A Development Fund was set up to provide grants, run by ICAIC which continues to produce in-house films too. The Fund has given opportunities to a greater diversity of film-makers including emerging young directors to develop their projects.

The Cuban national cinema industry, spearheaded by ICAIC, is not without huge challenges today but is still recognised as a visual and ideological reference point in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Trish Meehan for CubaSi Autumn 2023 magazine

Main image from ‘Por la Primera Vez”For the First Time’) a short documentary about mobile cinemas in the 1960s.