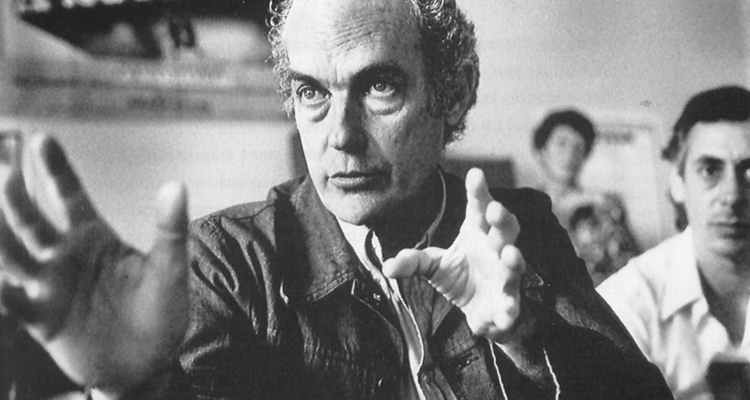

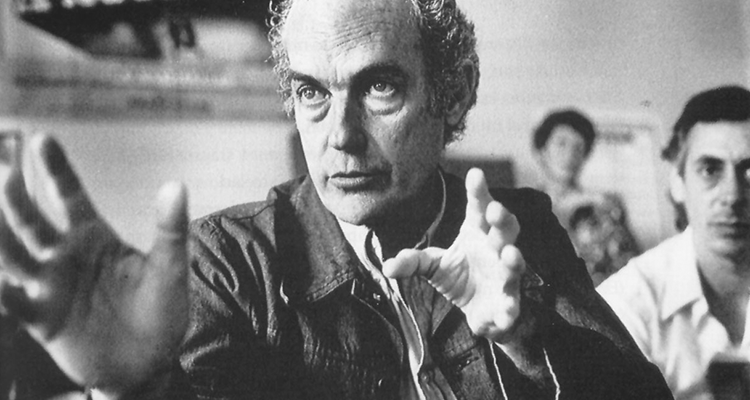

“For a long time, every time they asked me about my profession, I was ashamed to say that I was a film director, because they did not exist in our country. When I said it, many thought that I was directing or managing a cinema, and they asked me which one. Eventually, trying to avoid this confusion, I said that I was a filmmaker…” Tomás Gutiérrez Alea

Finding in cinema all the expressions of art that infected his artistic spirit, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea (Titón) became one of the most outstanding Cuban film directors of all time. Today we stop to remember his legacy as a cult filmmaker and a must-study filmmaker on the 25th anniversary of his death.

Nourished by Italian neorealism, after a stay at the film school in Rome, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea found in this artistic genre the appropriate capacity to create a national cinema, given the urgency of being able to look with a critical eye and tell the reality of Cuban society. Fuelled by this energy, the documentary ‘El Mégano’ (1955), directed by Julio García Espinosa with Alea’s collaboration, emerged. This was, without a doubt, a documentary that marked a ‘before-and-after’ in the history of Cuban cinema.

When the Revolution arrived, Alea was part of the team that together with Alfredo Guevara formed the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC). In the early 1960s he presented ‘Historia de la Revolución’, the first fiction feature film released by the newly created ICAIC. Likewise, the first promotional poster produced by the Institute was for this film, the work of prolific designer Eduardo Muñoz Bach.

Driven by passion and fury to create a truly authentic cinema with its own identity, in the sixties Alea gave the nation films of great historical and social value. Using jokes, drama, comedy, a society that was in constant change, and the dilemmas faced by people, were explained. These were films such as ‘The twelve chairs’ (1962), ‘The death of a bureaucrat’ (1966) and ‘Memories of underdevelopment’ (1968).

Most of Alea’s films portray a society in motion, maintaining that critical neorealism within cinema throughout his career as a filmmaker, based on constructive, realistic criticism and, of course, with a high degree of authenticity. For example, his film ‘Strawberry and Chocolate’ (1993) became one of the first to talk about homosexuality in national cinema.

Titón throughout his life managed to make more than 20 films, including feature films, documentaries and shorts. He showed a lucidity in highlighting the social, economic and political problems of the country. It is enough to go back to his filmography of the first years of the Revolution to realize how truly free his cinema was.

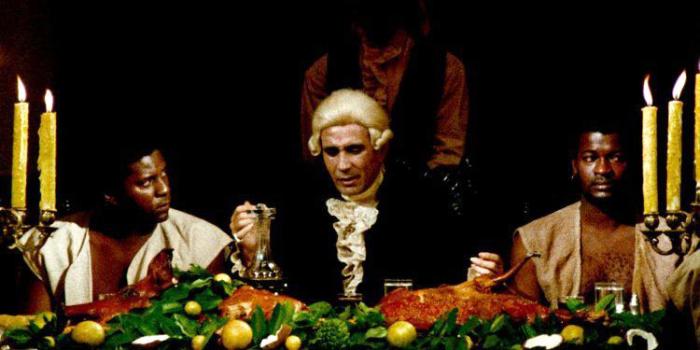

The Cinemateca de Cuba has devoted special attention to the restoration of his works, and it now has restored five fiction classics and a documentary: ‘The death of a bureaucrat’, ‘Memories of underdevelopment’, ‘A Cuban fight against demons’ (1971), ‘The survivors’ (1978). ‘The Last Supper’ (1976), and the documentary ‘The Art of Tobacco’ (1974). Returning to Titón is to return to the wonderful reality of our cinema.

From CubaCine on the 25th anniversary (16 April 2021) of the death of Cuban film director Alea

Link to the original article in Spanish by Cubacine April 2021

Screen Cuba is showing

‘The death of a bureaucrat’ (1966) by director Tomas Alea

This classic film satirises how red tape in the revolution affects the everyday lives of its people. As a badge of honour, a model worker is buried with his labour card in his pocket. But his widow needs it to claim the benefits she is entitled to. The film traces the family’s often hilarious Kafka-esque efforts to recover the precious document in the new society where everyone is treated as equals. But should that extend to the dead? Alea, known as the father of Cuban cinema, presents a radical new vision of a universal theme containing notes of many cinematic icons from Chaplin and Laurel & Hardy, to Brecht, Eisenstein and Buñuel.

.