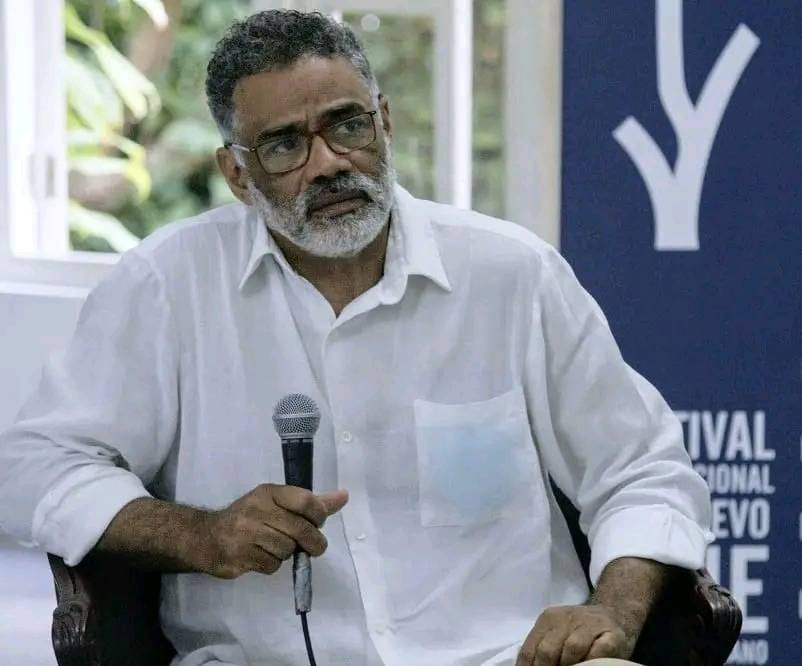

Jorge Luis Sánchez, director and screenwriter, director of ‘El Benny’, was founder of the National Federation of Film Clubs of Cuba, artistic deputy director of the Latin American ICAIC News and promoted new and young voices and defended Cuba’s cultural diversity.

Director Jorge Luis Sanchez who sadly died in January 2025, studied teaching and started as an amateur filmmaker when he was 18. He was the founder of the National Federation of Film Clubs in Cuba, together with Jackie de la Nuez and Tomás Piard, and fought hard to create an amateur film movement that the ICAIC finally recognized in 1978, when a group for young people emerged supported by the Institute and coordinated by critics José Antonio Rodríguez and Mario Piedra.

In 1987, Jorge Luis Sánchez organized film workshops with the Hermanos Saíz Association (national network for young artists of all artforms), a space that brought together numerous young people whose entry to ICAIC to work with the best professionals seemed impossible. These workshops gave the young people materials not suitable for use by professional cinema: cameras, moviolas, rolls, lights. Thus, with an expired film and imperfect cameras, Jorge Luis Sánchez made his first documentaries.

In 1981 he first worked professionally as a camera assistant and then became an assistant director in well-known films of the eighties such as Baraguá (José Massip, 1986), Clandestinos (1988), with whose director Fernando Pérez he forged a very long professional relationship, and the co-productions Un señor muy viejo con unas alas enorme (Fernando Birri, 1988) and The Summer of Mrs. Forbes (Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, 1988). He participated as assistant director, with Orlando Rojas (Supporting Roles, 1989) and again Fernando Pérez, with Hello Hemingway (1990).

As part of the work of the film clubs, Jorge Luis Sánchez made his first documentary in 1985, Los ríos de la mañana. In 1991 he worked with Santiago Álvarez at the ICAIC Latin American News as deputy director and participated in the production of issue number 1,987. In 1992 he was appointed, after his constant battle for recognition of amateur cinema, president of the Film Workshop of the Hermanos Saíz Association. A few years earlier he had made Amigos, in 1987, and Un pieza de mí, in 1989, documentaries where two of the essential characteristics of his later work are already revealed: the sensitivity for the dramatization of everyday life and the fictionalization of reality.

In contrast to some of the cinema made by the ICAIC in the eighties, Un pieza de mí arises as an important sociological inquiry, which never loses the human trace, on the concerns, worries and conflicts of that sector of youth known as the geeks. The film was awarded the special jury prize at the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana and selected by critics among the best documentaries screened that year.

1990 and 1991 were fundamental, because in addition to participating in the production of the ICAIC Latin American Newscast, number 1,987, he directed two of his best documentaries, Where is Casal? and El Fanguito. Winner of the UNEAC Caracol Award for Best Documentary, the 13-minute black and white short film Where is Casal? was co-written by the director together with the poet Mariana Torres, with photography by Rafael Solís and editing by Félix de la Nuez. The director and co-screenwriter is inspired by the search for the remains of Julián del Casal to propose an approach to the life of the unfortunate and misunderstood poet. It must be said here that the idea of this film served as the basis, almost thirty years later, for the fiction feature film Buscando a Casal.

Also in black and white, with a script by the director together with Alexis Núñez Oliva, Félix de la Nuez and Benito Amaro, cinematography by Rafael Solís and editing by Félix de la Nuez, El Fanguito, with a duration of 12 minutes, approached the unhealthiness of the neighborhood located on the banks of the Almendares River, in the heart of Havana and next to El Vedado. The filmmaker selects testimonies full of contradictions, dramas and hopes that reveal the humanity of his protagonists. In the Revista Cine Cubano, number 148, the filmmaker assures that he wanted to free the viewer from specialists, objective narrators, intertitles, voice-overs, etc.:

“My appropriation of the conventionality of the documentary was reduced to the austerity of fixed framing, synchronous sound and a musical conception closer to the sound effect than to the music. In the dark room, expressive resources would make it easier to show, rather than demonstrate. To ask, rather than to answer. And I was standing there. More as a witness than as a prosecutor or defender, without allowing intermediaries between my real characters and the viewer.”

The journalist Raciel del Toro,…writes that “the filmmaker set out to rejuvenate a national documentary that at that time was stylistically in decline within the official sphere. Like the filmmakers of English free cinema in the early sixties, Jorge Luis Sánchez participates in a reaction to the comfortable cinema that was being made at the end of the eighties in Cuba. El Fanguito was selected by the national critics among the best Cuban documentaries of the year, won the second Coral Award at the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema and the Directing Award at the Latino Festival in New York.

The decade of the Special Period, the nineties, finds Jorge Luis Sánchez waiting to access fiction, in an interval of paralysis for Cuban cinema. However, he continued to produce, directing documentaries such as El cine y la memoria (1992), Atrapando espacios (1994), about the artistic personality of the troubadour Raúl Torres, and the beautiful tribute to Elena Burke that is Y me gasto la vida (1997), which I discovered because Jorge himself invited me to see it in a small video room, during the Workshop of the theoretical brawl that I recounted before. The best thing about the documentary was the atmosphere of complicity that the filmmaker managed to create with the interviewee, who was never too prone to questioning dialogue in front of the camera. On the other hand, in the insistence on the mockumentary, the filmmaker’s anxiety to venture into fiction once and for all was perceived.

While making these documentaries, Jorge continued to work as an assistant director. He worked again with Fernando Pérez in Madagascar (1994), which marked him decisively in the use of visual metaphor without renouncing critical content. He then worked in advertising in Venezuela, in the TV series Culto a los orishas (1999) and directed the making of Kleines Tropicana (Daniel Díaz Torres, 1997). These two also delimit the filmmaker’s area of thematic interest in terms of raciality, deep Cuban culture and music.

He began the 2000s with the making of the documentary Las sombras corrosivas by Fidelio Ponce, still with general production by Carlos de la Huerta, photography by José Manuel Riera (who also accompanied him in some of his most important fiction films), editing by Pedro Suárez, music by Frank Fernández and a cast led by Teherán Aguilar in the role of Fidelio Ponce. The documentary represents another of the director’s obsessions: the relationship between high and low culture, between marginality and art, because the painter is remembered as irreverent, even marginal. The film also shows how the values of authenticity present in his painting are manipulated by tourism and by counterfeiting merchants.

As a very coherent continuity with his past as an essential figure in the development of independent cinema in Cuba, Jorge presided over the newly born National Exhibition of New Filmmakers, later called Muestra Joven…

Finally, in 2006, he managed to carry out a long-cherished project, a sort of biography of the brilliant Cuban musician Bartolomé Maximiliano (Benny) Moré in the fiction feature film El Benny, which won a resounding success with the public and numerous international awards at the Locarno, Caracas, Havana, Santo Domingo, Oaxaca and Asunción festivals. The research he undertook to make El Benny led to the production of a four-chapter documentary series entitled Benny Moré, la voz entero del son, also released in 2009, which some critics and music historians, such as Rosa Marquetti, consider the most complete and profound audiovisual about the history and contributions of the biographer.

The greatest virtue of El Benny consisted in the ability of its makers to give us a very particular image, that of Jorge Luis Sánchez and his team, of an immortal artist, an image that revives in the public the memory of the eternal creator, and with this is enough to give liveliness and poise to a film. Because cinema is also a means of confirming one’s own cultural values, and El Benny is an example of the ability of Cuban cinema to ratify and recreate one of the most complex and notorious icons of Cuban popular music.

Also in 2009 he premiered, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the ICAIC, the documentaries Never Will Heresy Be Easy and Within Fifty Years. Both dedicated to cultural rescue, the first contains a review of the history of the ICAIC and the cultural policy of the Revolution throughout those five decades. The second is also encouraged by the celebration of the ICAIC’s half-century of existence. Through a workshop, figures related to the institution narrate important experiences to four young filmmakers who will analyze the complexity of the works created by their predecessors around animation, production, audience and documentary, respectively.

The consecration of Jorge Luis Sánchez as a theorist and historian of Cuban cinema, which he was also one, and one of the best and most rigorous, came in 2010, when Ediciones ICAIC published Breaking the tension of the arch, which filled a tremendous void in the historiography of national documentary cinema. Shortly after, he dares to try to fill another void and presents the anti-racist musical Irremediably Together (2012), which well analyzed contains some of the lessons of what should be done, or not, while conceiving a musical in Cuba, and then ventures again into historical cinema to address a subject as complex as the birth of the republic in Cuba libre (2015).

With photography by Rafael Solís, editing by Luis Ernesto Doñas, music by Juan Manuel Ceruto, sound by Osmany Olivare, and with interpretations by Jo Adrian Haavind, Isabel Santos, Adael Rosales and Manuel Porto, among others, Cuba libre talks about “two children who, after the defeat and departure from Spain, at the end of the War of Independence, they live intensely the moment when the Americans behave like an occupying army.” According to journalist and writer Marilyn Bobes, the film “has the merit of offering a non-Manichean vision of the sad episode that prevented the Liberation Army of the Cuban mambises from enjoying a victory alienated by the intervention of a power whose true purpose was to turn the island into a colony or neo-colony, a fact of which not all Cubans were aware, as can be seen in the film. (…) Jorge Luis Sánchez’s script exudes a patriotic breath that only a Cuban could have impregnated him. Rara avis is Cuba libre in the context of a cinematography where criticism of current affairs displaces the history of the nation. Especially, when that story is shown to us in all its difficult contradictions, including those of raciality, so present from the point of view of the characters, and the identification that occurs between black American soldiers and the Cuban population and mambises of the same color.”

In 2019, Jorge premiered the biography Buscando a Casal, a project that the filmmaker had been preparing for many years. At the time of its premiere, I wrote that it was an “important film in the tradition of Cuban cinema inclined to historicism, as it recovers some essential themes in any biography of the always controversial poet, namely: the freedom of the artist, the rebellion against the dictatorial power of the Spanish government and the validation of friendship.”

Jorge Luis Sánchez also taught at the ICAIC, at the International School of Cinema and Television (EICTV) and at the Faculty of Audiovisual Media Art (FAMCA). In addition, he wrote articles about documentaries, independent cinema and the most relevant and least recognized creators of the ICAIC, especially those with whom he had worked, such as José Massip, Fernando Pérez, Fernando Birri and Orlando Rojas, among others, recounting his experiences with them, with the same passion with which he undertook everything, in the pages of the Revista Cine Cubano. He died while he was writing, teaching, preparing another documentary series and venturing into the pre-production of his new film, Performance.

Extract from Jorge Luis Sánchez: A Nonconformist Filmmaker and Some of His Footprints – Revista Cine Cubano